Disabilities and Optimistic Futures (Part 2)

Seeing ourselves in a just future.

“Nothing is more punitive than to give a disease a meaning - that meaning being invariably a moralistic one.” ― Susan Sontag

While teaching a forensic science class, I recently ran a roleplay scenario where the student played a lead investigator to a potential crime. They asked about the scene, questioned witnesses, and examined potential evidence. The clues seemed to point toward foul play: a frustrated ex, a storage locker dispute, and a missing knife. But each lead unraveled under scrutiny; she was at work, the house mess came from the storage mix-up, and the knife was simply in the dishwasher. In the end, there was no murder at all.

He had just slipped.

The opening quote in this article comes from Illness as Metaphor and AIDS and Its Metaphors, later referenced in the more recent Everything is Tuberculosis. Both share the same central message: the notions of “natural deaths,” “poetic diseases,” or victims who “shouldn’t have done xyz” are absurd. People search for a reason why. But often, there is no moral reason at all,

only chance and germs.

Finally, game designer “Rabbit Rabbit” draws a parallel between QAnon and tabletop role-playing games like Dungeons & Dragons. In a game, players sometimes fixate on objects that were never meant to be clues, such as a pile of oddly shaped planks that look like an arrow on the map. QAnon, as a conspiracy theory, weaponizes that same tendency that encourages followers to treat every seemingly validating image as proof of their beliefs. Addicted to specific news channels, my grandparents still will mention crime in any given topic of conversation, because there is always an example and thus it must be as rampant as people say. There was never an arrow,

just broken wood.

In part one of this article, we explored how conspiracy theories and fear-mongering have painted autism as a new kind of monster; a problem that must be “fixed.” It is far easier to identify someone who lives differently, frame that difference as a threat, and imagine a cure than to accept the alternative: there is no grand conspiracy or undiscovered solution and that’s boring. Genetic differences occur at random or are hereditarily passed down. There is no single “optimal” way to be. It takes some taxes to support healthcare. Understanding mRNA just requires paying attention in biology class. And saying “let’s support each other” feels too simple compared to chasing some supposedly better, better, better more exclusive path that’s always just out of reach.

Platitudes sounds a little too cringy for our likings. Things like "work hard and you'll get ahead" or "love thy neighbour" always make us queasy and we can no longer say them without the tiniest hint of irony. Or worse, we make a point about mocking anyone who dares to adopt these sentiments unironically. In other words, we're always going 'meta' out of the fear of being deluded into taking anything too seriously. We believe that we're looking at everything from a point of elevation, permitting us to make judgements while being critically detached.

- Robin Waldun, Critique is The Mood of the Internet

Cynicism wins over Occam's razor because it feels more intelligent to take the lesser traveled road. We try to defeat a disability when portraying a future because it must be something to be defeated right? Surely everyone wants to hear, walk, talk, read, and think the way I do? Isn’t that just better? Or even so, maybe they have differences that are better, or should be perceived as such so they can feel better about being worse. Maybe that person has a superpower even.

“Imagining someone as more than human does much the same as imagining them as less than human.” ― John Green, Everything is Tuberculosis

As an asterisk, as discussed in the previous article, anyone should, of course, be free to see and define their own identity and own disability in whatever way feels right to them (The Individual Model of Disability). This is a critique on outsiders defining an individual or group as a monotype and applying labels onto another.

Now that the prefacing is up, let’s look at the power of optimistic futures with some examples and strategies for integrating disabilities into sci-fi media.

In-Group and Out-group

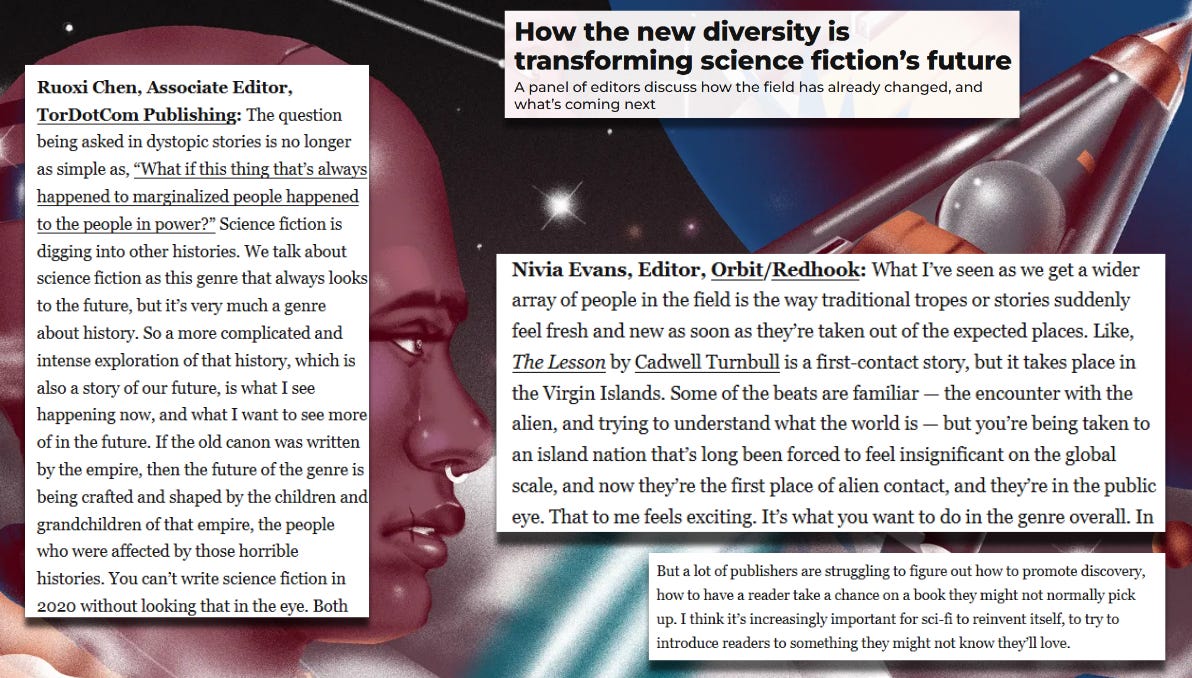

One important point to address is the general divide I’ve noticed in discussions about minority representation in stories. One perspective argues that, even if we are not part of a particular community, we should still include characters from diverse demographics to make our stories more representative of society (not necessarily like an old 90s kids cartoon checking boxes however). The other perspective cautions that writing outside your own lived experience can easily lead to stereotypes and tropes.

My own inclination leans toward that representation matters, even when the author is an outsider to the community. However, this approach demands research, thoughtful consideration of the character’s role in the story and common tropes, and, ideally, direct conversations with people from that community. It also may differ based on the specific story being told. That all said, this is only one viewpoint in a much broader and more complex conversation, with many layers of nuance out there.

Falling in and out of Stereotype

In Star Trek: Strange New Worlds, Season 1, Episode 3 (“Ghosts of Illyria”), the character Una Chin-Riley is revealed to be Illyrian, a species banned from the Federation because of their genetic engineering practices. Over the course of the episode, she proves herself to the crew, and despite regulations, they choose to stand by her as supportive allies. It feels like the episode is neatly wrapping up until she records a personal log:

“Dr. M’Benga stopped hiding today, just a little, for once. I did too. I told Captain Pike the truth about myself and he defended me, told me I was exemplary; that he would fight for me. So, why do I feel terrible? What if I hadn’t saved all those lives; would the captain feel the same? What would he do if I wasn’t a hero, one of the good ones? When will it be enough to be an Illyrian?”

When a stereotype exists, there will inevitably be people who, by coincidence, fit it. They may even feel pressure to alter aspects of their identity to distance themselves from that stereotype. I’ve had students who loved and hated Big Bang Theory. While Sheldon is a stereotype of an autistic person and the creators have never actually called him as such, there were students that related to him, both in personality and experience. They still felt represented by this stereotype. While I am not recommending to go out to your novel’s Google Doc and start writing in stereotypes, aspects behind this nuance of experience are important to discuss.

There are also common commonalities behind marginalized experiences and shared frustrations between various members of a community, such as the moment in the video below where Geordi La Forge expresses exasperation at having to repeatedly explain his vision apparatus. While it is nice and kind to explain and teach someone about a topic, if it is not your job to do so, it should never be expected.

Optimistic futures don’t always mean having perfect attitudes, from anyone involved. However, it can be used to help acknowledge ongoing issues, and empower us to see a world where it’s easier and less frowned upon to treat ableism itself more than the disabled individual.

Problematic Tropes

The Plot Device - When a disabled character exists mainly to advance the story rather than as a fully developed person. Their disability might be used to create drama, motivate another character’s actions, or explain a plot twist, but the character themselves is not given depth, agency, or complexity. For example, a Deaf character in The Last of Us.

Peripheral Characters - Disabled characters who remain on the edges of the story and have little impact on the main events. They may be included for “diversity” but are given minimal development, limited screen time, or no significant role in the plot beyond being background figures. Note that this aspect of tokenism isn’t always a problem. Sometimes it’s just enough to show many types of people exist much like our own society, even if they’re not in the forefront of the story (depending on the story told), and much of this issue exists in portrayal. In Star Trek many background crew members are shown with prosthetics or assistive devices, but their stories are almost never explored. This trope can be highly contextual.

The Supercrip - A character whose disability is portrayed as something they must “overcome” in either extraordinary or simple, futuristic, technological ways, often by achieving superhuman feats. This trope frames disability as a challenge to be conquered to inspire able-bodied audiences, rather than as a normal part of life. Jake Sully in Avatar.

The Tragedy - A disabled character whose main narrative purpose is to evoke pity or sadness. Their story centers on suffering and loss, suggesting that their life is inherently less fulfilling because of their disability, and often ends in death or permanent misery. A sub-trope of this is the ‘Tragically Disabled Love Interest’.

“We hear ‘you’re bound to your chair, you’re confined to your chair,’ it’s all these things that make a wheelchair seem like it’s a bad thing when really a wheelchair is a tool. It’s something we use for independence and freedom. It’s a tool, just like a wrench, just like your armor, or your shield, or your sword in fantasy stuff.” ― John Loeppky, Tabletop Games and Accessibility

The Inspirational Invalid - A character whose disability exists primarily to inspire others, usually non-disabled characters or the audience. The focus is on how brave or positive they are despite their “limitations,” reducing them to a source of moral uplift rather than portraying them as complex individuals.

The Savior - On a similar note to the last trope, when I tell people the populations I work with in my 1:1 teaching programs, they remark how brave I am. I am not, it’s just easier and more fun to work with one student than managing classes of twenty. I enjoy how much we can differentiate content for a specific student at a time, and all in all I feel a lot less stressed.

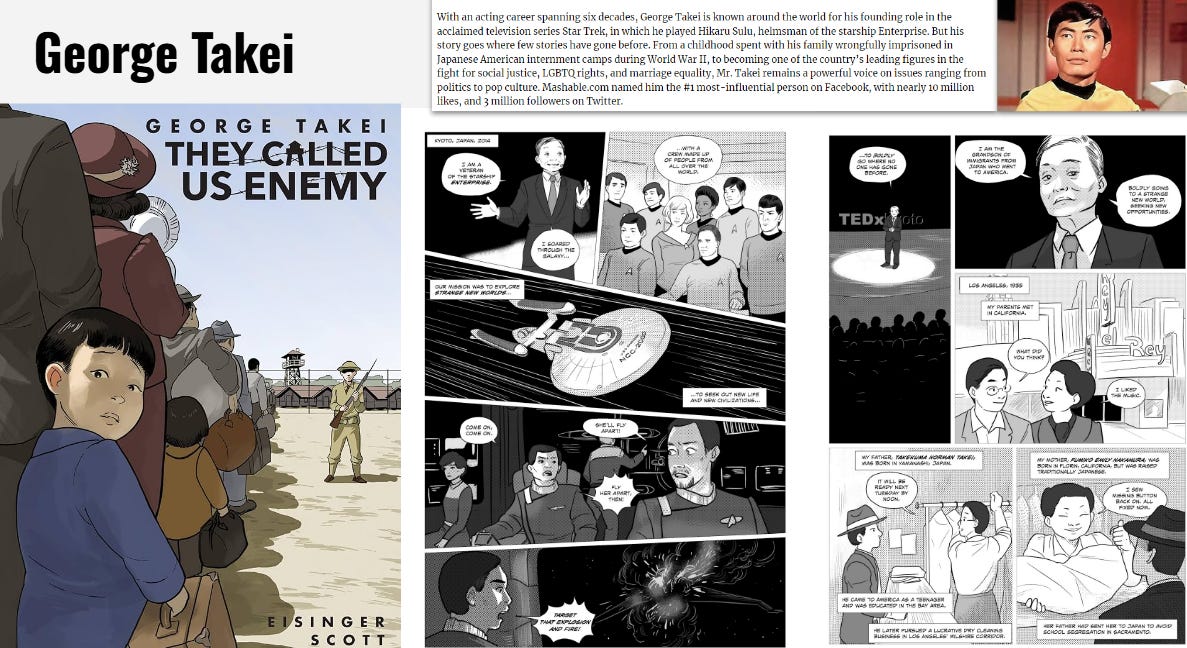

“Disability is strongly present throughout Butler’s body of work, from her published texts and her early notes and drafts to her unfinished and unpublished works such as Blindsight and Parable of the Trickster. Disability appears not only in the form of disabled primary and secondary characters, but also in terms of thematic concerns, often in direct relationship to more commonly discussed matters of race and gender.” ― Sami Schalk, Octavia E. Butler as an Author of Disability Literature

Octavia Butler’s work doesn’t always stagnantly avoid the above tropes, but it often frames disabled characters as complex, autonomous individuals whose identities are not defined solely by their impairments. The “right” way to write disabled characters involves giving them agency, nuanced motivations, flaws, and growth that exist beyond their disability, while portraying that disability as one aspect of a full life rather than a problem to be solved or a symbol to be decoded. It does not mean erasing the disability, since it is part of the character’s lived experience, but a story also does not need to always cast the disability as either the central obstacle to overcome or the defining source of heroism. The disability is not the enemy. Common experiences within a group can additionally be explored, but it should not always fall on a disabled individual to address these issues alone.

Assistance Without Assimilation

The issue I often see with AI sign language interpreting startups is twofold. First, American Sign Language (ASL) is a highly contextual language where the setting, situation, and people involved all shape interpretation. If I were Deaf and signing, “Hey Thomas, I can’t believe we’re both in Boston,” there could be several contextual cues embedded in that moment. Facial grammar is also a key part of ASL, and sub-varieties like Black Sign Language have their own nuances. I have yet to see a technology that addresses these factors well.

Second, many of these technologies are developed by hearing-led teams with a “cure” mindset, aiming to “fix” deafness rather than respect Deaf culture or the language itself. They often overlook first integrating existing infrastructure in language education, such as teaching ASL in classrooms beyond just the ABCs or a few words like “bathroom.”

We rarely hear the same kind of tech-world excitement when someone says, “Oh my gosh, we can finally understand French people!”

When writing the future, please by all means incorporate new technology for the disabled, but consider if the tool is for them or for society to tolerate them.

Fears of the Faker

When talking with both adults and students, I sometimes hear people bring up the faker. You know, the person on TikTok claiming to have a certain neurodiverse condition when “we all know” they do not. Honestly, while it can be annoying, I do not find it worth much energy. This is just my opinion, based on my own experience as an autistic person. Unless someone is actively spreading large amounts of harmful misinformation, the impact rarely justifies the outrage.

As representation improves, for example I have only started seeing autism depicted in cartoons within the past few years, these situations are bound to happen. It may become a bigger concern in the future, but right now it is not the primary threat. If someone is simply quirky and calls that “autistic,” yes, it can invalidate some people’s experiences. I would not fault anyone who disagrees with me here about this whole section. But these cases are relatively rare, and fueling a reactionary backlash often does more harm (i.e. to the autistic person being called ableist and fake) than the so-called “faker” ever did.

“You know, I struggled for years to get through Training. I had to work and pay my own way. Washed dishes, worked in kitchens. Studied at night, learned, crammed, worked on and on. And you know what I think, now?" "What?" "I wish I'd become a plant earlier.” ― Philip K. Dick, Piper in the Woods

Finally, we have a really big issue with attitudes towards self diagnosis. First, someone who is self-diagnosed is not receiving the same accommodations or benefits that a formal diagnosis provides in schools or workplaces, because those require official paperwork. Second, there are many barriers to getting diagnosed. These include biases related to race and gender, medical professionals often and commonly dismissing symptoms (“you don’t look autistic,” “you make eye contact so you cannot be autistic”, “Everyone does that”), lack of local or national healthcare resources, ideas that autism is a growing pandemic when we’ve been here the whole time it’s just being noticed now, outdated diagnostic categories (in some countries Asperger’s is still the only available label), the misconception that autism only exists in children, and the significant financial and emotional costs of the process.

For some, getting a formal diagnosis can be affirming and helpful, and that is a valid choice. Others know themselves well enough, have done the research, and choose not to go down that path. Both are valid. And in a climate where public figures like RFK Jr. are compiling lists of autistic people, policing self-identification seems misplaced.

If someone believes they are something, and it helps them better understand and adapt to their own life without harming others, by all means there are no Gods or Kings here. Feeling you may be a part of something, committing research, and talking to others is always going to be the first step, regardless if someone is something or not.

Fears, Generalized

I do a lot of work on prison abolition. What can justice look like outside the context of prisons and police, and really rooted in community accountability, healing, and restorative ideas of justice? Science fiction is a perfect testing ground for these issues, because the vast majority of people can't imagine a world without prisons. ―Walidah Imarisha

In neuroscience, we have an interesting way of processing new information. Back in college, I participated in a wellness research study that demonstrated this through an activity called “Late for Lunch.” In it, groups were given a simple scenario: you’re meeting someone for lunch, but they haven’t arrived yet. List as many possible reasons why in the time provided.

Most people started with negative assumptions about the other person: “They don’t like me,” “They were in a car accident,” or “They’re sick.” Only later, or less often, would more neutral, positive, or self-reflective explanations appear: “I’m in the wrong place,” “They’re stuck in traffic,” or “They’re stopping to buy a gift.”

The brain’s stress response often works in a similar sequence to how it evolved: fight, flight, freeze, or fawn first; then emotional processing; then the rest of our higher-level thinking.

A first reaction: “Should I call them five times? Why aren’t they answering? They must hate me!” A more practiced response: “They’re not here yet. Maybe they’re in traffic. I’ll wait ten minutes, then call. In the meantime, I’ll look around in case they can’t find this spot.”

When I teach wellness classes to students, much of the content sounds obvious - but applying it takes active, deliberate work.

I’ll make this final point: There are ways for us all to live well that don’t arrive easily, but that doesn’t mean we can’t put in the work for a better future. When we imagine optimistic futures ahead, they provide us with a model to grow towards and exist in. While there is time and room for cynicism, judgement, and authoritarian questioning, there must also be time for the nice, boring explanation.

We are just waiting in traffic.

Other Notes and Resources

I specifically was seeking out topics of dyslexia shown in science-fiction, and among the vast discussions on Percy Jackson, I really couldn’t find an actual dyslexic science fiction character. If you know of an example, please reach out.

“Liking What You See: A Documentary” is a great short story from my favorite author Ted Chiang, that resonates with the face blindness side of myself.

“To Be Taught, If Fortunate” by Becky Chambers has some excellent themes of mental wellbeing during alien discovery, that resonated with some toxic ideas I’ve found among scientists (i.e. the culture of needing to be obsessive over your field in professional and personal life).

“Accessing the Future” by Djibril Al-Ayad (Editor) and Kathryn Allan (Editor) holds a great collection of speculative stories of disability and mental illness in the future.

Here’s a Google Scholar link for more journalistic articles on this subject of ableism and sci-fi.

Kampala Yénkya by sadpress is a tabletop game that has participants imagining an optimistic future on what Kampala will be like in the year 2060.

‘Star Trek’ Adviser Discusses Sci-Fi’s Real Science at NASA Goddard